Social Justice and Freedom of Speech

I came to the ACLU with racial justice as my primary passion.

For me, subjugation and invidious discrimination on the basis of skin-color was the major civil liberties violation I saw.

I was also formed, as a 9-year-old fan of the Brooklyn Dodgers, by the struggles of Jackie Robinson to end the color barrier in major league baseball.

I first learned about Jim Crow segregated hotels and restaurants by listening to radio broadcasts of the Dodger games, and finding out that when the team played in St. Louis, the Dodgers’ black players couldn’t stay or eat with the rest of the team. I didn’t learn that in school, or from my parents. I learned it from the Dodgers’ broadcaster, Red Barber (who was from Mississippi). And I hated it: those were our guys, my guys.

Free speech? Not so much.

If you had asked me back then, I would have said I favored free speech. But like most Americans, I usually had my own speech in mind, or the speech of people who agreed with me. I hadn’t given much thought to protecting speech I hated. On the streets of Brooklyn where I grew up, the reflexive response to bigotry and insult was a punch in the nose or, if you were outnumbered, running away. More speech was not an option anyone considered when confronting bigotry.

It was not until I came to the ACLU when I was nearly 30 that I really confronted the idea that in order to protect my own right to speech I had to protect everyone’s right, because the true antagonist of speech is power and if speech wasn’t free, then government would get to decide whose speech to permit and whose to prohibit. And I began to understand: why would I want people like Joe McCarthy or Richard Nixon to have the power to decide whose speech to permit? Much less Donald Trump or William Barr? Why would anyone want their opponents to be able to decide if they could speak their mind?

As Hosea Williams, one of Martin Luther King’s lieutenants, once said to an astonished television audience: if I allow the Georgia police to ban a peaceful Klan rally in Atlanta on Monday, they would gain the power to ban me and my efforts to register blacks to vote in Fulton County on Tuesday, Wednesday and every day thereafter. So I will oppose efforts to ban the Klan from peaceful speech because that is the best way to protect my own.

Or as I once told a group of black university students in the 1990s who favored hate speech codes: if such codes had been in effect in the 60s, Malcolm X, not David Duke, would have been their most frequent target. Because the only thing that matters with speech restrictions is who decides how to apply them. And usually it isn’t vulnerable minorities—whether political, racial, or sexual.

Today, many people calling themselves “progressive” believe that social justice and free speech are antagonists, because they have been confronted by so much bigoted speech. But historically and politically, the opposite is true: every movement for justice in America—the labor movement, the birth control movement, the civil rights movement, the gay rights movement and the Black Lives Matter movement today—has depended on freedom of speech to initiate its movement and keep it growing.

Freedom of speech and social justice are not antagonists. They are allies—crucial allies.

Margaret Sanger knew it. Joe Hill knew it. Martin Luther King, Jr. knew it. And as the saintly John Lewis once said: “Without freedom of speech and the right to dissent, the Civil Rights movement would have been a bird without wings.”

Freedom of speech is the air beneath the wings of social justice. Always has been. Is now.

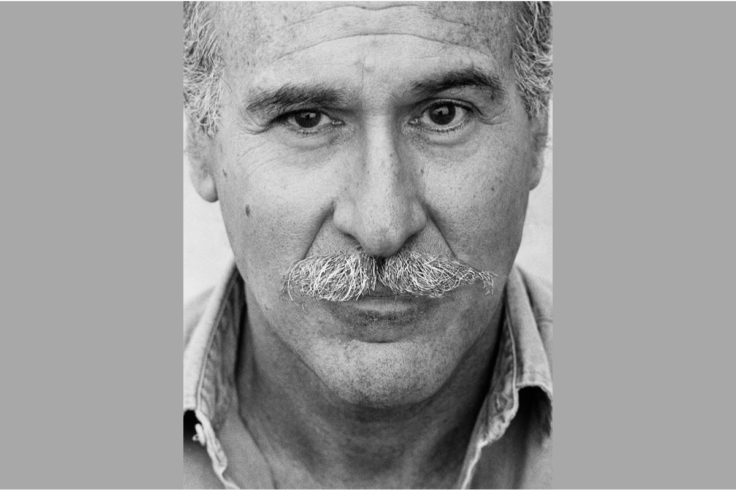

-Ira Glasser, Former Director of the ACLU

Ira Glasser is the Hugh M. Hefner First Amendment Award honoree for Lifetime Achievement for his fierce defense of freedom of speech and expression during his 23-year tenure as Executive Director of the ACLU.